History Talks: Protect us from our protectors

Prayers in the 17th century pleaded for safety from the very soldiers meant to protect them, and none knew the reality of why better than the residents of Kežmarok.

Everyday prayers in the 17th century included phrases such as "… and protect us from the kuruc (anti-Habsburg rebels) and from the labanc (imperial soldiers), O Lord!”

It was quite understandable that people said these prayers, as both the kuruc and the labanc represented a huge burden for most inhabitants of what is now Slovakia. Soldiers needed to eat, drink and stay somewhere. In most cases, this burden fell to the villagers or burghers – the people who lived in the place the army happened to be.

The fact that the militias harmed people more often than those they were expected to protect them from was well known by the people of Kežmarok. This town in the Spiš region was in a very complex situation in the course of the 17th century because of the predominance of Protestants among its population. If it was threatened, the imperial Catholic army came to help the town but were not very friendly towards its Protestant residents.

If the town was occupied by Protestant rebels, the situation was no better. This was the case when in the first decade of the 17th century Stephen Bocskay and his troops appeared in Kežmarok. Bocskay, the rebellious duke, took advantage of his friendly terms with the Kežmarok castle lord, Sebastian Thököly, and with his help enforced a special tax on the citizens, amounting to 1,000 guldens. One house was worth about 60 guldens.

Kežmarok’s citizens thus had to pay both to the emperor and the rebels. After Bocskay, another rebel nobleman entered this town at the foot of the Tatra mountains – Gabriel Bethlen. The town council decided, to make sure and prevent looting or some other tax, to donate a gilded pot worth 127 guldens – the value of two houses at that time. Moreover, they put 225 guldens in the pot.

Kežmarok did not avoid the rebellion of Juraj Rákóczy I either, who came to the town in 1644. Rákóczy summoned the town representatives before a special court where he decided that every burgher had to redeem their lives with a considerable amount of money.

Slovakia was gloomy during the turbulent 17th century; no wonder the country longingly yearned for peaceful times.

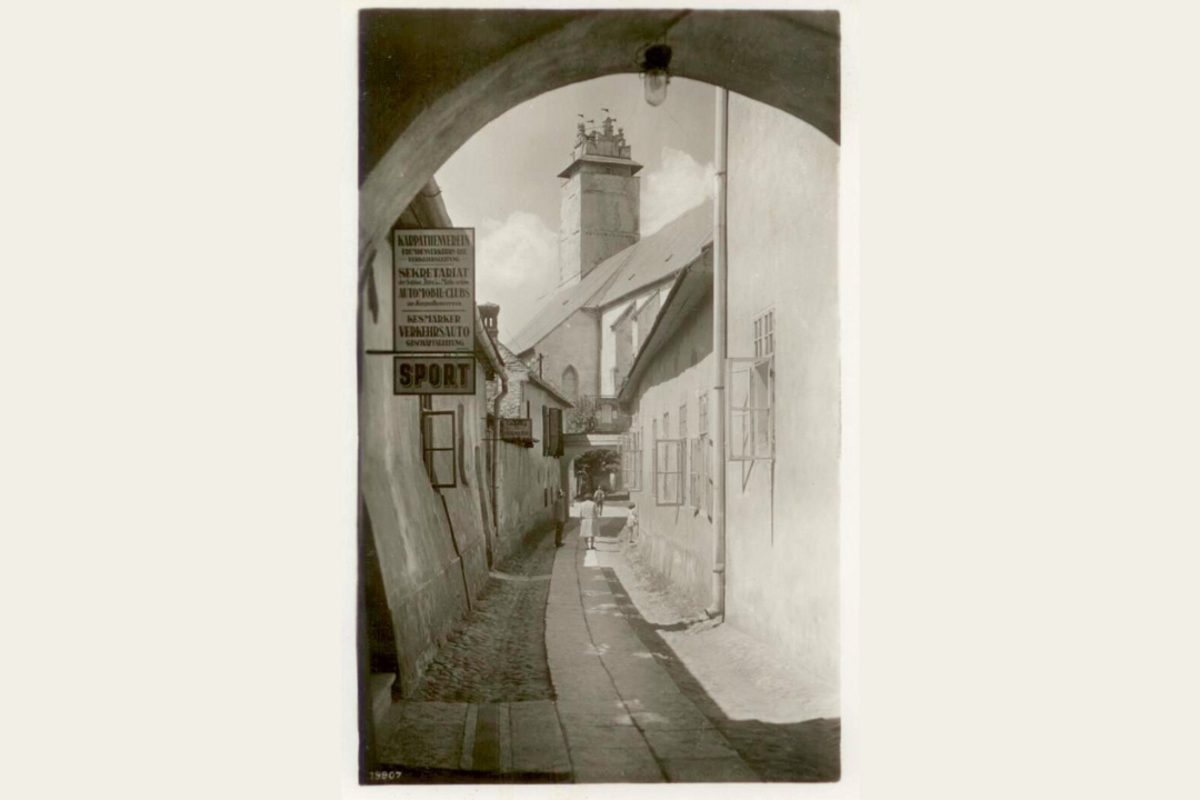

In this postcard from the 1930s, we can see the mediaeval street of Kostolná ulica. The sign on the left announces that the Kežmarok car club resided in the house with thick walls.

This article was originally published by The Slovak Spectator on March 30, 2015. It has been updated to be relevant today.

Related

Share this page

Guest Posts by Easy Branches