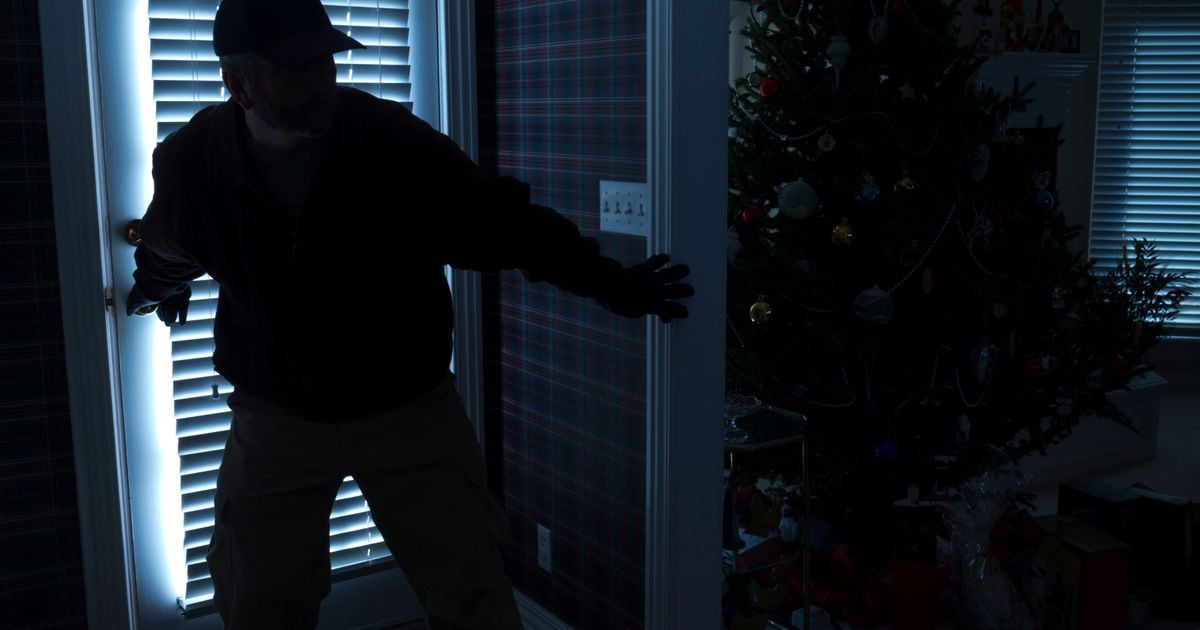

'The night before Santa was due, burglars invaded our safe space like human cockroaches'

'Peace of mind's 24-carat sparkle was ceded to the darkness when our home was breached on Monday last'

They ransacked the house, stealing irreplaceable keepsakes, yet the most scarring aftershock in the wake of a Christmas burglary came at a deeper, existential level.

Peace of mind's 24-carat sparkle was ceded to the darkness when our home was breached on Monday last.

The night before Santa was due down the chimney, intruders smashed a back window and, like a plague of human cockroaches, invaded our safe place.

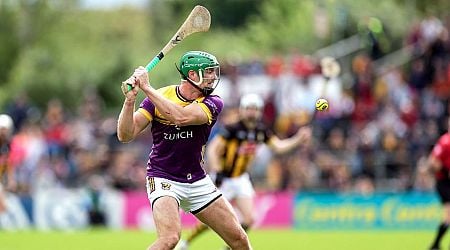

READ MORE: '€1,000 Christmas gift vouchers for RTE staff? There's one for everyone not in the audience'

READ MORE:'You'll know Coldplay are in town because you'll see Chris Martin sit beside you and stare at you'

Arriving home to a shards-of-glass welcome mat, to the stuff of your life spilling from overturned lockers and thrashed cabinets, delivers the kind of disabling gut-punch Tyson Fury would love to have inflicted on Oleksandr Usyk during last week's heavyweight title fight.

It surprised me just how jolting an experience a visit from the darker corners of society can prove.

There is no Robin Hood romance, no Ocean's Eleven glamour for the winded, frightened and hopelessly discombobulated victim.

For some it might awaken their inner Dirty Harry, a go ahead make my day, desire for vengeance. For most of us, the immediate sensation is of sinking into quicksand, the unblemished skies of life clouding over suddenly, ominously, darkly.

Shakespeare sagely wrote that "the robbed that smiles steals something from the thief." Unfortunately it isn't so easy to summon a grin when the overwhelming impression is of being a hostage to hopelessness.

Even now, five days on, the deeply unsettling aftertaste is difficult to cleanse from the palate. It feels like a violation, this knowledge that hooded, gloved figures despoiled and pillaged our humble suburban castle, the padding between us and the outside world.

There is no scent, yet, still, their polluting presence invades the nostrils. No visible footprint, yet we perceive them walking amongst us, trampling on every waking hour.

Though Christmas FM played its upbeat chorus in the days after, it could not completely drown out the echo of glass shattering. The sense of physical loss can, of course, be significant.

A quick preliminary audit revealed that among our uninvited friends' opportunistic plunder was an engagement ring, a wedding band, and - most heartbreakingly - some items belonging to my late mother, artefacts of memory beyond price.

The latter felt, in its sheer badness, almost like the desecrating of a grave. Many of you will be familiar with the consolation of holding onto a ring or necklace that once adorned the finger or hung from the nape of a lost loved one.

The value of the piece is not the intrinsic one, but rather it lies in the feelings it awakens, the blessed way in which opening a jewellery box can set the bereaved, a son, daughter, a mother or father, a widow or widower free on a nostalgic joy ride. A bracelet that might not fetch 25 quid at a car boot sale can be worth more than The Cullinan Diamond to those who remember its original owner.

In the wake of a burglary, the unpleasant reminders scorch their way into the consciousness. Makeshift plywood drilled into a doorframe where the glass pane used to reside, an ugly, unavoidable souvenir, one that continues to scar the terrain of normalcy.

The surreal experience of a Garda Technical Team officer arriving on Christmas Eve in what everyone present recognises will almost certainly prove a futile search for a smudge of a fingerprint that might yield a clue to the perpetrators' identities.

The knowledge that they - whoever they might be - were in your house, your bedroom.

Even the Christmas tree, standing sentinel by the fireplace, can seem a little startled in such a disfigured ambience. I found myself plotting a break-in of my own, a clumsy amateur-psychology attempt to enter the minds of those who, each time they clock in for a disdainful shift, cannibalise a part of their victims, the corner where contentment and serenity reside.

It is the barren rock of a burglar's empathy that is most confounding.

The question is largely rhetorical, but do they ever pause, even for a moment, to consider the pain they inflict, the trauma that is the toxic fruit of their labour? When such pernicious events occur at this time of year, the damage done seems somehow even more extreme.

How many parents are compelled to make panicked 999 calls upon discovery that Santa's concealed bounty had been appropriated in the run up to December 25th? What malevolence of the soul permits somebody to steal a child's Christmas?

The same twisted psyche is at play when elderly people are conned out of their life savings or, worse again, violently beaten in their own homes by a burglar enraged by the few meagre euro the poor soul has hidden away.

That those responsible for such unconscionable pulping of innocence and decency seem so frequently to be on bail having been charged with similar offences in the past merely serves to bring a besieged legal system into the sharpest focus.

For those on the receiving end, it can feel as if the culprits are essentially laughing at the law, holding two fingers up to society and announcing themselves as untouchable.

Then there is the drumbeat of "What ifs?" What if we had stumbled upon them in mid-pillage? In that case, what if they carried a weapon, what if we saw their faces? What if they come back?

It is not only to those of a particularly nervy disposition that the days and weeks after can feel like a surrender to a mild form of post traumatic stress. Any noise disturbing the 3am darkness can reduce somebody living alone and recently burgled to feelings of impotent terror. When they do manage to sleep, maybe the neon light of an alarm flashes continually in their subconscious.

And yet, for all of the above, for all that the experience can and does shave any sense of security into flimsy, crumbling wafers, our family's abiding memory of the past week is of the essential and towering decency of people. One friend telephoned at midnight, offering to cross the city with some planks and a drill to patch up the mangled doorframe.

Another wanted to know if we needed cash, accommodation, replacements for any presents that had been taken. A neighbour we barely know called with a bottle of wine, a deluge of WhatsApp offers of assistance poured in, flooding our inbox.

It was lovely, life-affirming stuff, a reminder of the quiet goodness that is the powerful glue holding society together. A reassurance at a traumatic time that even the most skilled and callous thief can never crack open the safety deposit box where the best of the human spirit resides.